Japanese Woodturning - Part One

I’ve noticed a small, but growing interest in Japanese turning within the green woodworking community of late, so I thought I’d write about what I’ve learned in more detail. Although I let the genie out of the bottle a while ago when I posted about my process of making and learning to adopt this tool, safety concerns held me back. It’s great that others have started using this machine—it’s inspiring—I get it, however, like learning to ride a bike or skateboard you’d be a fool to attempt going no handed or dropping in on a 12’ vert ramp after your first day figuring out how to ride either of them. Please give my following perspective about safety serious consideration.

Over the past 10 years I’ve taught a lot of people to turn with hooks on the pole lathe and I can only remember one or two students who understood right away how to use them without catching. Pole lathes are relatively safe—if you do catch, the lathe just stops. Electric lathes do not stop. Turning on them is significantly more dangerous and this fact needs to be taken seriously. Every year electric lathe accidents cause numerous head trauma injuries and a few deaths—although rare—I’m not joking. There are numerous risks. Catching a tool is one of them. It’s not something to take lightly and a very sharp broken tip of a hook tool will go flying—and at great speed. This doesn’t happen when using a pole lathe. I know some of you inspired folks don’t want to read this, but I’m advocating that you learn to turn with hooks on a pole lathe first. When you can turn 20-30 bowls in a row without catching once, then you are ready to try to use hook tools on an unstoppable electric lathe.

This recommendation is also for folks that have experience using modern lathes and gouges too. Nearly all the students I taught that were previous bowl gouge turners had a hard time unlearning the techniques of gouges. In fact if you unknowingly approach hook tool turning with some of the rules of gouge turning—like keeping the shaft of the tool parallel or level with the centers—you will catch, every time. Hooks don’t work that way. They are two completely different techniques.

Now that I’ve done my due diligence, let’s get into it. I’ve broken down the information into two posts. This post will cover the history and context of this style of turning as I see it. In the following post I will cover what I learned while studying woodturning in Japan. I’ll include plenty of photos of the lathes and tools.

An old lacquered wooden bowl, folk museum Takayama.

Wooden tableware has a rich and long history within the Japanese culture. We share that history here in the West, but the widespread use of woodenware largely ended a few generations ago. There are some exceptions—one being the large diameter bowls produced en masse by bowl mills here in the States. But in Japan the timeline is unbroken and this is one of the reasons why I traveled there. I wanted to learn from a culture that has been using woodenware continuously for 10,000 years. I was also interested in learning more about the craftspeople and businesses that were producing and marketing huge quantities of wooden tableware annually.

I believe that the main reason for the continued use of wood in Japan as a material for tableware is intrinsically tied to urushi lacquer—a filtered and refined tree sap that polymerizes into a strong, long lasting, waterproof and tasteless finish. An ancient lacquered wooden bowl was found in an excavation in which the wooden core had rotted away, but the urushi shell remained and was nearly the same quality as it was when it was applied. This is truly remarkable. There have been other wooden objects finished with urushi that have been found from the Jomon period some 10,000 years ago. These examples are a testament which support urushi’s reputation as the world’s best natural finish. It’s nothing like the stinky, half rancid, gummy linseed or walnut oils that are in common use in the green woodworking scene today. As I’ve explained in a past blog post, the superiority of urushi doesn’t come for free. It takes dedicated training to learn to use and cure (polymerize) properly because it’s concentrated urushiol. Read that post here.

Originally wooden bowls—all over the world—were hand carved but as turning technology developed and spread the production of bowls moved from being carved to being turned on the lathe. To understand the Japanese style lathe and turning techniques I have to briefly explain the origin story of the lathe or at least the current hypothesis.

It is accepted that lathes are one of the most important machine tools ever invented. They are in a class of axis-oriented tools like the supported spindle used for spinning fiber (10,000 BC), the bow drill for drilling holes (5000 BC), the potters wheel for forming clay into vessels (3500 BC), and the wheel (3500BC). Unlike those other axis-oriented tools, the lathe could produce the parts of other machine tools. This is of paramount importance. Lathe-turned parts are integral to a vast majority of our machines. Even devices like the smart phone with no moving parts couldn’t be produced without machines with turned parts, nor be put together without other turned parts—very small screws. This is the era of the lathe. To me the lathe is an axis mundi.

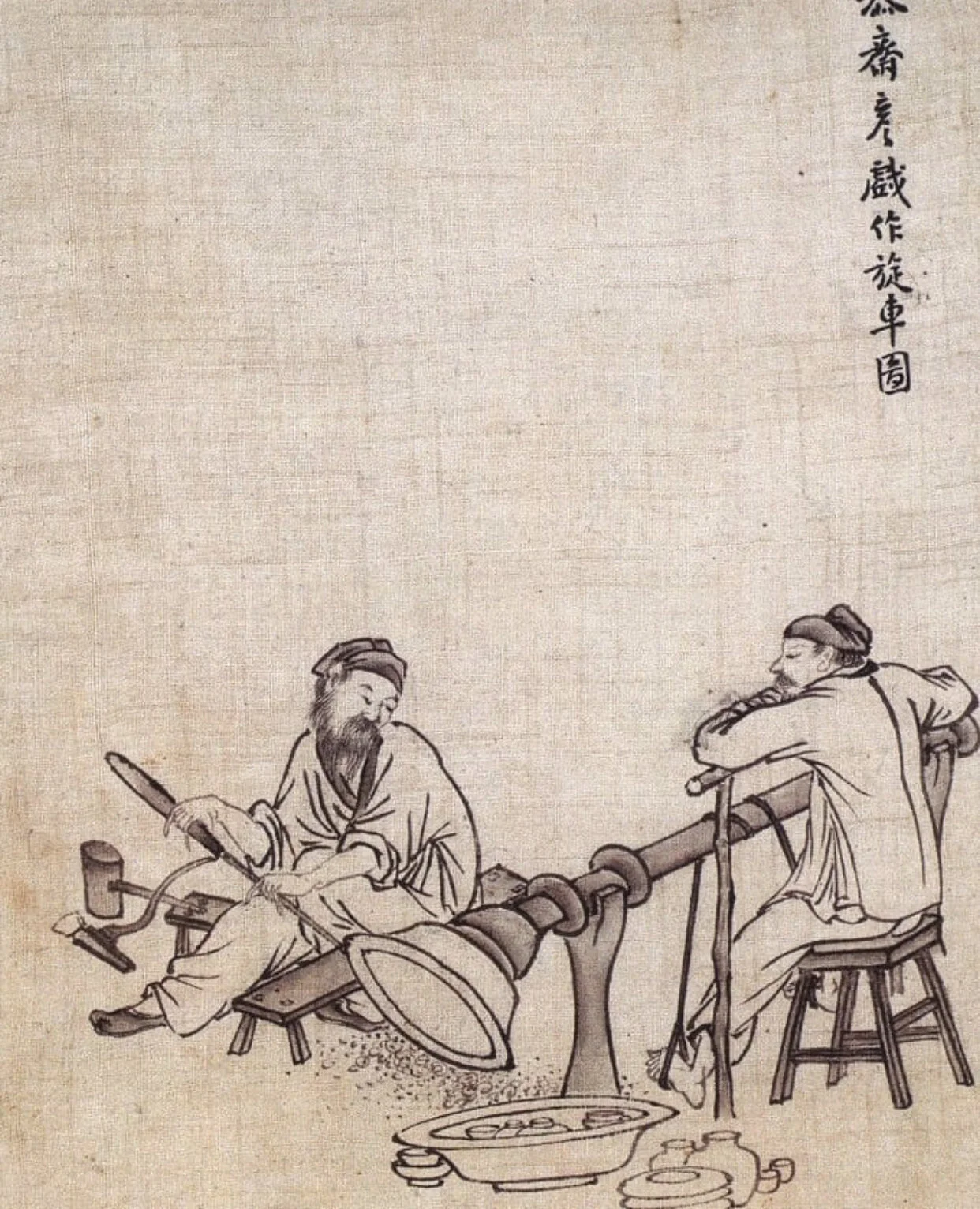

Photo from History of the Lathe, Woodbury

It is widely believed that lathes existed in some form between 3000-1500 BC. A turned stone button from 2000 BC may be one of the earliest evidence of turned objects known. A recent reexamination of an archeological find from Egypt confirms that wood turning goes back to at least 1500 BC. It is assumed that the earliest lathes were reciprocating lathes—meaning that the object being turned spun back and forth. The oldest known image of a lathe is a type known as a strap lathe. This image is from an Egyptian stone carving dated from around 320 BC. The strap lathe is powered by a hand held rope or strap which is wrapped around either the work piece or a drive shaft, which is suspended between two centers. An assistant pulls back and forth on the strap which reciprocates the object or drive shaft. A second person, the turner, applies an edge tool to the spinning wood thus cutting or ‘turning it’. Another type of early lathe is a bow lathe. Like the strap lathe a cord is wrapped around the workpiece or a drive shaft, but instead of being hand held, each end is fixed to a bent bow of wood. The bow is then pushed and pulled, thereby turning the piece in a reciprocated motion.

Suspended-type, bow driven lathe. Photo from Hand or Simple Turning, Holtzapffel

Suspended-type, strap-driven lathe. Photo from Hand or Simple Turning, Holtzapffel

Each of these lathe types have their pro’s and con’s. The bow lathe requires only one person to operate while the strap lathe requires two. But the bow lathe isn’t powerful enough to spin large and heavy things like a strap lathe can. Western lathes (pole, modern electric, great wheel, etc) and the various Asian lathes (I’ll get to those in a bit) are likely all descended from these archetypal lathes.

When researching lathes and their history, I’ve come to think that there are two important distinctions that should be made with early lathe designs—the drive system and the axis system. These characteristics are a little technical to explain so bear with me.

First is the axis system. All lathes need to establish some sort of axis to spin anything. Historically there were two ways this was achieved. One way is to suspend the material to be turned between two centers (conical pointed pieces of metal). I call this type the suspended-type. The other type is to suspend a drive shaft between two bearings and then fix the material to be turned to one end of the shaft. I call this the shaft-type.

Shaft-type lathe powered by a foot-driven strap. Image from a Chinese scroll.

The second distinction is the drive system. All lathes need some sort of power to drive them—to make them spin. This has historically ended up being done with a drive belt or strap instead of some sort of gear system. The drive belts/strap either reciprocates with a bow, strap or spring pole or spins continuously with flowing water, a treadle lathe with fly wheel, or an electric motor.

When axis systems and drive systems combine, the possibilities of different lathe designs are realized. The bow and the spring pole lathes are examples of suspended-type lathes driven by reciprocating action. With suspended-type lathes the drive strap must be wrapped around either the work piece or a mandrel which is a small shaft attached to the work piece (like bowl turning on a pole lathe) The downside is that this also means that the drive strap must be wrapped again on each new piece to be mounted on the lathe.

On the other hand, continuous motion lathes like the great wheel, treadle, water driven or electric lathe typically use a shaft system. There is no need to rewrap the drive strap to each new piece to be turned because the strap or belt is wrapped around the drive shaft. It would be technically challenging to wrap and tension a continuous motion drive strap or belt with each new work piece on a suspended-type axis lathe. Historical examples reveal that shaft-type lathes were powered by a variety of drive systems, but only the suspended-type lathe employed reciprocating drive systems.

Shaft-type strap-lathe with pedals from China. Photo from Hand or Simple Turning, Holtzapffel

Although the modern Western lathe has a tail stock which enables an object to be suspended between two centers, it is still being driven by a motor which is connected to a shaft and therefore it is a shaft-type lathe.

The current standing theory is that lathe technology was developed somewhere in the near Far East and spread from there. It’s likely the bow and the strap lathe spread into Europe and evolved into the spring pole and the other types of lathes found in Europe. The lathe also traveled East, through China and Korea and eventually to Japan sometime around 700 AD. From what I can tell the main Asian lathe was a strap driven shaft-lathe. There are examples of very interesting strap driven shaft-lathes in China which are operated by foot peddles instead of an assistant. Here is a nice video of one in use. It’s worth your time. I also saw one of these on display in Japan, although slightly different in design. I’d love to travel around Asia to learn more about their turning history—or even Russia…whose turning traditions are more similar to Asia than the West in many ways. I think this branch of the lathe’s family tree is fascinating and perhaps overlooked in the West.

Japanese Strap Lathe, Turning Academy, Yamanaka-Onsen

In Japan the strap driven shaft-lathes were used up until very recent times and in some remote places up until electric motors were introduced. These strap lathes were used by traveling itinerant turning family groups in the heavily forested mountain regions. Here is a cool clip from a 1976 documentary highlighting them. One of these turning areas is in Ishikawa prefecture. This area has been one of Japan’s major woodturning centers since the late 1500’s. In 2018, I visited the small town called Yamanaka-Onsen with my wife, Jazmin, and friend, Masashi. It was there I studied with a master turner named Takehito Nakajima. I’ll share more about the visit in part two. Yamanaka is also home to Japan’s only wood turning technical school. Students come from all over Japan to study there. There are also a few lacquerware companies that call the small village home.

If we compare the pole lathe with it’s lathe bed, semi-fixed tool rest, and tail stock (which acts as a second center) to modern Western electric lathes, it’s not hard to imagine how these lathes are interrelated. The modern electric lathes used in Yamanaka today also have striking connections to the earlier strap driven shaft lathes that were used just a few generations ago. The mobile strap lathe has no lathe bed, no tail stock or second center. It employs a movable tool rest which the turner, who sits on the ground, makes cuts from. This strap lathe has power in both forward and reverse directions because the assistant pulls each end of the strap in turn. This power combined with the absence of a tail stock allowed the the turners to develop a style of cutting that could work equally well in either forward or reverse directions. My guess is that this style of turning goes back as far as that particular lathe design does. For comparison, the pole lathe and the Western continuous motion lathes have power to cut in only in one direction. While I have reversed my pole lathe by wrapping the strap the opposite way for trick cuts with hollow forms, this technique was likely not in common use in the pole lathe’s heyday. Western-style turning was predominately done in the forward direction. More recently this changed with the invention of the variable frequency drive or VFD. I won’t explain that here, but it allows the motor to change direction with the flip of a switch instead of rewiring it.

One of my teachers, Takehito Nakajima turning on a Yamanaka style lathe. He is hollowing an end grain bowl in reverse.

“modern” Yamanaka-style lathe, shaft lathe driven by flat belting. Turning Academy, Yamanaka-Onsen

The turning technique of cutting in either forward or reverse direction and the design of the lathe without a lathe bed (and consequently a tail stock) and with a moveable tool rest is what sets Japanese and other Asian turning apart from Western turning. When electric motors were adopted for Japanese turning, the lathe design retained the turner’s ability to continue using the same techniques and traditions they employed with strap lathes in the past. This is why the modern Japanese lathe looks like it does.

In the next post I’ll discuss the two lathe forms I learned on while studying in Japan. I’ll also go in depth into the different tools they use and techniques that are hook specific.

Assorted turning tools, Turning Academy, Yamanaka-Onsen